(Betsy the Gremlin is a self-appointed Dialogue Doctor. Everyone says she’s good at writing dialogue and by gum she wants you to be good at it too!)

Part One of Many; Leave the Actors Alone

Something I am guilty of doing in my screenplays and have to actively fix in later drafts of work is over-directing the actors. Adding too many ‘umm’s and notes. Not the worst no-no in screenwriting etiquette, but not a great look for anyone. It’s a habit that makes sense; you know how the scene is supposed to play out in your head, and writing it with every pause and tone clearly marked is comfortable and safe. Arguably it’s great for a first draft! There is no misinterpreting your words and meaning. Except that’s the problem, isn’t it?

The truth of the matter is that if you’re lucky enough to have your screenplay made into an actual, on-the-big-screen project, the actors and directors will change things up monumentally anyway. The superfluous will be cut out. The more you try and translate every beat of your dialogue on the page, the more stuff actors and directors will slog through, hacking with their editing scythe all the while.

It’s not that they don’t like the dialogue necessarily, but (if they’re any good) they want to get to the emotional crux of the story. They can’t do that if they feel compelled to work in every ‘wryly’ and ‘umm’ verbatim over the course of the scene.

Look at the example below;

The dialogue is puppet master-like in the amount of directions. There is no room for interpretation. In fact, the more you direct from the page, the less likely it is for an actor to get to the heart of the matter and really bring the emotion necessary to make the scene work.

Finally, it’s hard to read. Yes, we know exactly what each character is sounding like, but what are they saying? The story is lost in the extra stuff added to the page. Obviously the dreaded “wryly’s” are all over the place, as well as the uhh’s and umm’s. Gross; we hate that. Giving this to a script reader will land you firmly in the ‘pass’ pile.

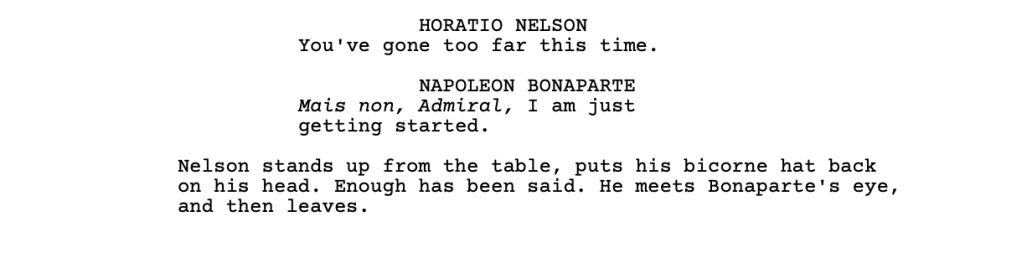

In the next example, I’ve tried to make it as un-directy as possible.

Even the second example, while better, probably could be trimmed down a little bit more (frankly, I just wanted you to all know that I knew what a bicorne hat was without looking it up). There is still control over the scene — the writer (me!) is saying when the scene ends, who leaves first, et cetera — but this example leaves a lot up to the actors and directors.

Are there days of shared history between the characters, or decades? Who is angrier? Who is in control of the conversation? These are vital questions you should be able to answer by using the context of the entire film; from something as simple as whether or not this scene is in the beginning or end of the movie, to the unnameable presence the actors have brought all on their own.

With the above example, we’re letting the actors be actors, and ultimately letting the characters be characters. The truth of the matter is that the first example was way easier to write than the second; one is a chokehold, the other is a release. If you’ve done your job, you can trust the other members of a movie to do their as well.

So, in the context of the ‘Dialogue Doctor series, let’s summarize what we’ve learned.

Leave a comment